As an excuse to play around with SwiftUI, I decided to work on an app idea I had years ago. A third party API I’d chosen for the app to depend on, I found, is free to use for n requests per day, and then a fraction of a cent per request after that, and the API key is sent with each request.

While pretending to sleep on my kid’s floor in order to get her to nap, I thought about how I could avoid exposing my API key such that a malicious actor couldn’t use the service at my expense, possibly racking up a significant bill, despite my own usage coming in far under their free request limit. (More on my solution in a later post.) After I felt confident about my solution, I decided to see what other apps did.

Web Security

Long time developers of web based services should know the cardinal rule of application security: all client traffic is untrusted and should be considered malicious. User input saved in the database should be escaped to avoid sql injection; user input that gets rendered on an HTML page should be HTML encoded to avoid running client side scripts; we encypt data in transit using HTTPS to avoid man-in-the-middle attacks, which could either reveal private data from the client, or alter it en route to the server.

I learned this not through academia, or through some awareness of common exploits, but by accidentally not escaping user input, and seeing the side effects first hand. (The first time I experienced this, for example, was when I didn’t escape users’ names on an early website I built, such that an apostrophe caused the raw SQL to get dumped for the user to see.)

Sadly, as I’ve worked with an increasing number of engineers raised using well established ORMs like ActiveRecord, or templating engines like ERB, I’ve seen more and more people forget this rule, and introduce vulnerabilities when they’re not protected by such a framework.

Mobile App Security

Ideally developers of mobile APIs treat traffic coming from apps as untrusted, since a mobile app is, afterall, a client. But in this case, there’s a new attack vector: the consumer of your app may act as a man-in-the-middle between app and client, so secrets shared between the two are at risk.

It is this vector that got me thinking about how to protect my API key while in transit. Specifically, if my app included its API key in requests to the third party API, even if encrypted in transit using HTTPS, the user could enable SSL proxying, using an intermediate certificate, which would allow him/her to see the unencrypted request.

Findings

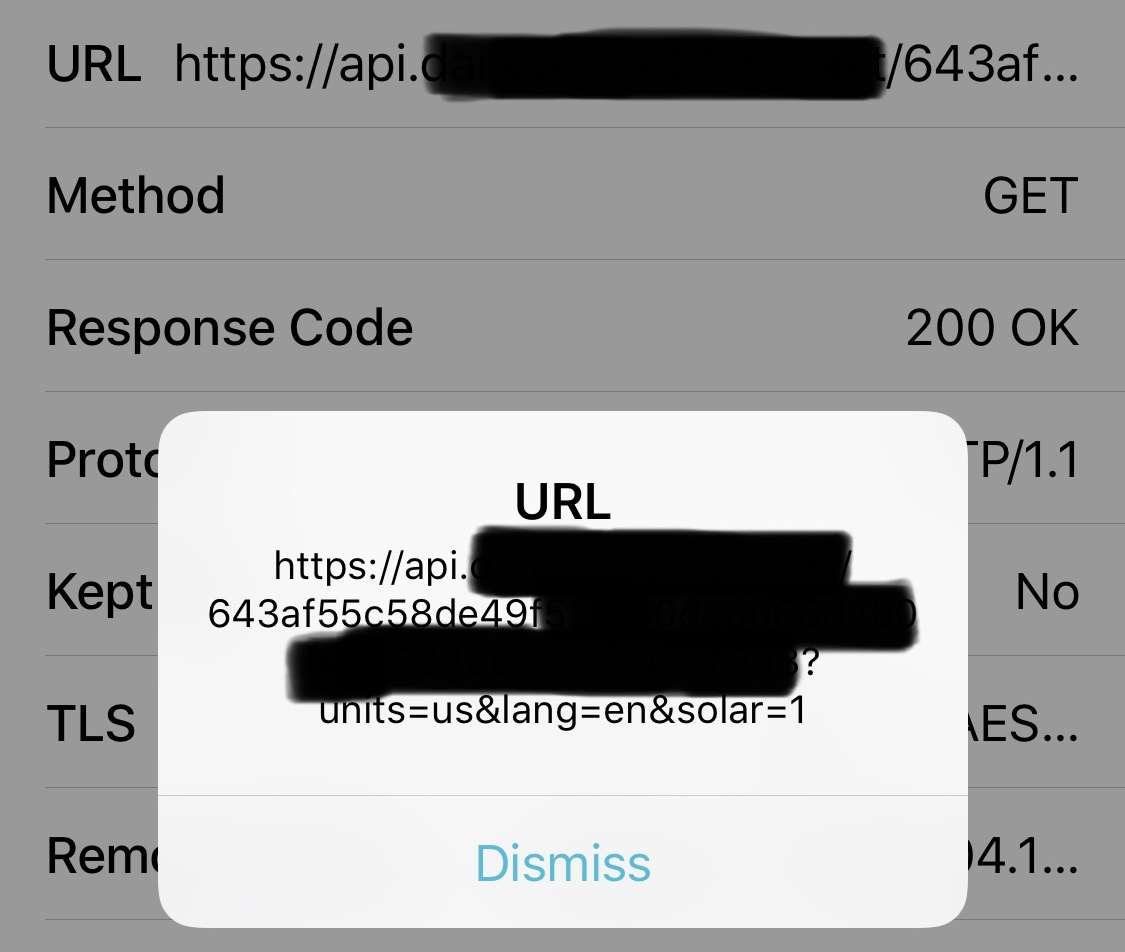

It took me about three minutes to switch on Charles, launch a couple apps, and log the unencrypted traffic. (I’ve done this before.)

The third party requires apps using their API to credit them on the app, so finding apps that use their API was easy. I checked two, which I won’t name, and the API provider’s own app.

Sure enough, all three were leaving the API key exposed:

So?

Like any vulnerability, there’s a balance between risk and cost to prevent. In reality, it’s extremely unlikely someone would steal my key to gain access to an already-mostly-free API. Preventing this requires running a server that authenticates the app somehow, and then proxies the request to the third party. This costs money, and, more importantly for my case, is another point of failure, and a set of things to maintain (domain registration, SSL certificates, scaling, etc).

However, if I were less honest, I’d also be able to use this API for free, since I have the service’s very own API key. ;)